When aspiring dungeon masters come to me for advice, they often end up telling me a variation of the following story.

“My players are enjoying my campaign, and they really like the plot and characters I’ve created. But every time they get into a fight, it really breaks the flow of play and ends up being drawn-out and boring.”

This is something that, as Dungeon Masters, we all experience at some point. Particularly at lower levels, the options for enemy combatants are often limited to gangs of goblins, kobolds, or some other generic, low-level antagonist. The solution I hear from most DMs is something along the lines of ‘run less combat encounters’. Respectfully, that’s a bullshit response. It would be nice if Dungeons & Dragons, the game that almost everyone is introduced to the hobby via, was a great balance of role-playing and fighting, but it just isn’t. While there are many great RPGs out there, such as ‘Call of Cthulhu’ or ‘Vampire: the Masquerade’, which are entirely about storytelling and atmosphere, D&D is not one of them. Few other systems have such a huge number of rules governing combat. Put simply, D&D is a combat-oriented game and most sessions will involve at least a couple of scraps.

The issue lies, not with the number or frequency of fights in your session, but with the way they are often perceived by both players and DMs. When a fight breaks out, we transition from a free-flowing, narrative-driven, verbal style of play, to a turn-based, mechanics-driven, rigid style of play. It’s jarring, kinda like those old Final Fantasy style JRPGs, where the overworld map fades away and we’re presented with a battle screen.

But here’s the thing, the fact that you’ve cleared all the crap off the table so you can stretch out your map and ready your minis, doesn’t mean you have to abandon the narrative elements that were present a moment ago. With a miniscule amount of prep, you can give a fight a sense of character and narrative charm that will leave your players feeling entertained and, with a little luck, like absolute badasses. So, with that in mind, let’s build a combat encounter together.

Your money or your life?

Here’s a classic 1st level D&D encounter. The players are travelling through the city streets at night when they find themselves in a dangerous part of town. They’re set upon by a small gang of bandits who aren’t interested in negotiation. Their demands are simple. “Hand over all of your money and equipment, or die.” The players don’t fancy being naked, and the bandits won’t listen to reason, so a fight breaks out.

As it stands, this is an incredibly boring fight. Four identical enemies, all just waiting to be chipped down to zero hit points. But here’s the thing, with about two minutes of preparation, this dull, mechanical experience can become a story in itself. The key to all of this is right there on the stat block.

In fifth edition Dungeons & Dragons, every monster and NPC has a dice value next to its hit points. I very rarely see DMs using these, which is a shame, because they can inspire you to create cool characters on the fly. Let’s roll some dice!

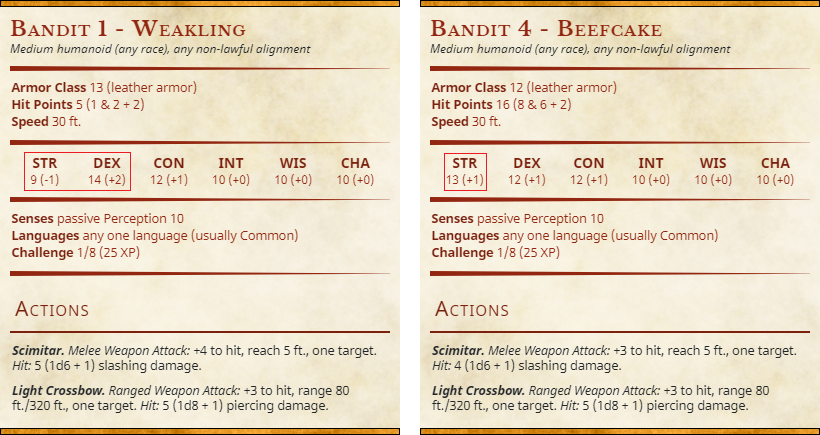

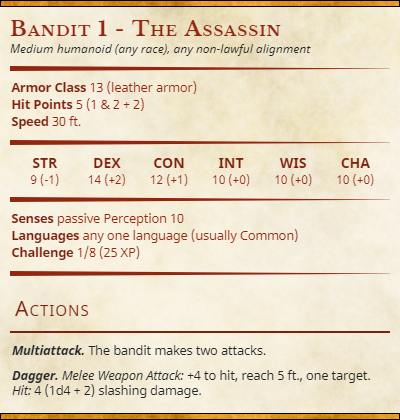

For each bandit I rolled 2D8 and added 2. They now all have different amounts of HP and we can begin to imagine how that might influence, not only their strategic attitudes, but also their personalities. It doesn’t make much sense to me that a group of guys with such varied thresholds for punishment would all have the same physical attributes, so let’s switch them around a bit.

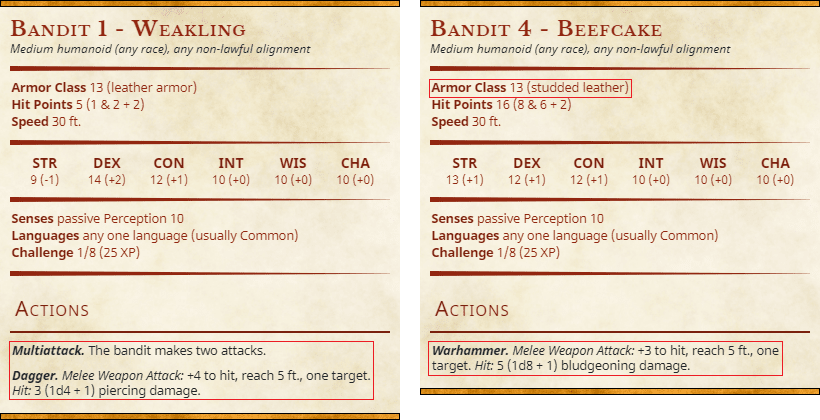

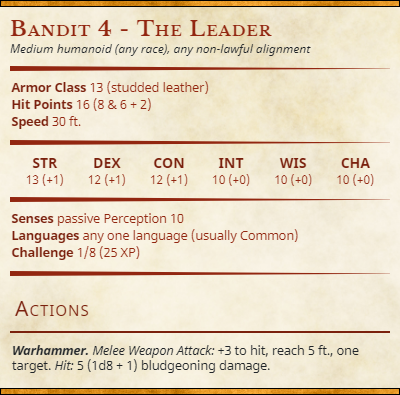

I’ve decided that our weakling is going to be the gang’s resident sneaky guy and that beefcake will be the gang’s brutish leader. Weakling’s DEX goes up by two so I offset it by nerfing his STR by the same amount. I want beefcake to be able to handle more than his underlings, so I simply buff up his STR. We can already see characters forming here. There’s no way two guys with such differing attributes would be identically armed, so let’s play with their equipment.

Our weakling now has a couple of tricks up his sleeve. I’ve given him two daggers, making him capable of dealing a significant amount of damage, providing he can get into position without taking any himself. His slightly higher DEX has also increased his AC to 13, giving him a fighting chance. As for the beefcake, his AC has also been boosted by an upgrade to studded leather armour. Furthermore, we’ve given him a warhammer, slightly increasing his damage-dealing potential. He’ll now provide a challenge for the party’s most heavily armoured member, who’ll need to protect any squishy casters from him.

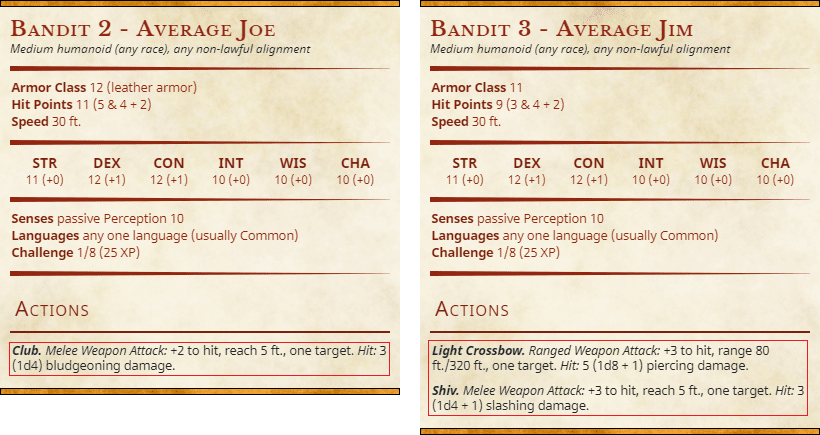

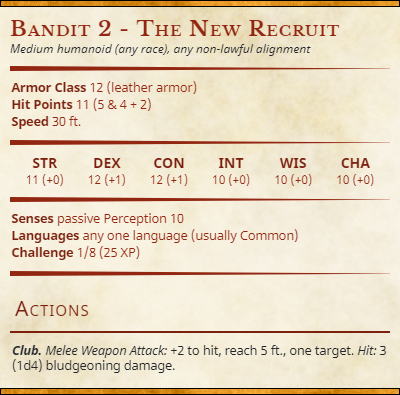

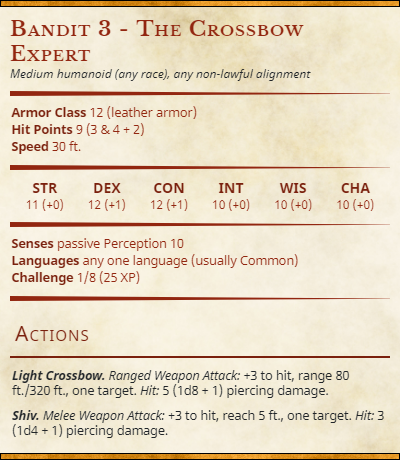

Now let’s turn our attention to Average Joe and Jim. While it would be perfectly fine to leave them as they are (after all, they’ve barely changed as it is), we’d be missing a great opportunity for diversity if we did.

So far, all of the enemies have had a damage increase, so I’ve decided that average Joe is a new member of the gang and hasn’t had the chance to get a decent weapon yet. He’s just carrying a lump of wood, which he uses to club people. This balances things out, but it also distinguishes him as less of a risk to the players. At 9 HP, Average Jim has slightly below the default 11 for a bandit, so he’s going to be the gang’s resident artillery expert. I’ve taken away his scimitar, leaving him with just a basic shiv (I used the standard dagger stats, but shiv sounds cooler.) Jim will only use the shiv if he has to though. He prefers to stay away from melee and fire his crossbow at enemies.

After what amounts to no more than two minutes’ preparation, we now have a nuanced and diverse gang of ruffians to throw at the players. Lets go over them.

Our assassin carries two daggers and prefers to engage party members who are distracted by his allies. Failing that, he will go for whoever is least heavily armoured, hoping to take them down before they have a chance to strike back.

The new recruit is nervous, poorly equipped, and prone to fleeing. He can see that he’s no match for the party and doesn’t want to die on the streets for the sake of a few gold coins. If he’s reduced to half health, or if the leader falls, he uses the disengage action and flees the fight. He’s also susceptible to intimidation attempts.

The crossbow-wielding bandit will use his movement to remain at ranged attack length from the party, firing a crossbow bolt at whoever he perceives to be the most likely to close the gap. If that happens, he pulls out his shiv and tries to dispose of his assailant as quickly as possible.

The leader of the gang charges immediately and engages whoever seems to be the most defensively capable member of the party. He hopes that by taking down a heavily armoured fighter or paladin, he can keep up the morale of his fellow gang members and scare the party into surrendering. He is too arrogant and stupid to flee, even when death is a certainty.

Tell them to go fluff it

As you can see, we now have a charming little band of brutes for the party to face off against. We could go even further, changing their race, skills, languages and other elements, and you should absolutely do that if you have the time/desire. But it certainly isn’t necessary, as the player’s imagination can fill in the blanks. All that’s left is to come up with a sentence or two describing them, enabling your players to gain an insight into what their strengths are. Something like the following.

As you near the end of the alleyway, four thugs step out of the shadows ahead of you. Their leader, a hulking man of at least six-and-a-half feet, brandishes a warhammer before setting his eyes directly at yours. “Hand over your equipment and gold” he demands, “or you’ll not be leaving this alley”. Behind him stand three others. One of them, a weed of a man in a filthy cloak, holds a cruel dagger in each hand and wears a sadistic smile on his lips. Next to him, a young lad, perhaps sixteen or seventeen years of age, nervously fingers a makeshift club. Finally, leaning against one of the walls is a fourth mugger. He taps a battered old crossbow against the brickwork, seemingly nonchalant to the whole affair.

This bit of fluff is key to the whole setup. While we’ve certainly crafted an aesthetically diverse group of bandits, we want those visual differences to inspire a tactical approach from the players. When your group tells war stories about their experiences in your world, they probably aren’t going to remember the individual names of the enemies they’ve slain, but they will reminisce about the time that they took out a dual-wielding assassin when he was inches away from ripping the wizard to shreds, or the Warhammer-swinging thug that just wouldn’t go down, no matter how many arrows they stuck in him.

Always remember, Dungeons & Dragons isn’t about winning, it’s about telling a story together. While you, as the dungeon master, are certainly the catalyst for that narrative, your players can and should be responsible for it as well. Never is this more apparent than in combat, where the creativity, assumptions and actions of the players will ultimately decide exactly how that chapter of the story is told.